The Case for Cash App as a Super App (Aspiring Super Apps #2)

A mini-series on apps that could be 'Super Apps'. This issue is focused on Square's Cash App

Housekeeping:

Happy 2021 to all! May all your ambitions, price targets, and indoor-dining fantasies come true.

Disclosure: I own $SQ. I also added a general disclaimer to the East Meets West about page.

This is the second issue in a sporadic mini-series covering the Super App ambitions of American tech companies. This issue will focus on $SQ and the Cash App

I’ve been excited about Square for a long time and finally bought the stock when it took a dip in March. Since then, I’ve spent time trying to understand where the company is going with the Cash App.

Introduction:

I’ve recently come across more companies trying to brand themselves as “Super Apps for X”, where X = finance, travel, entertainment.

I’ve come to think of these as ‘narrow super apps’. While there are great rewards for being a narrow ‘Super App’, these descriptions feel mostly like marketing ploys.

The Cash App is already well on its way to becoming a narrow “Super App for Finance” (aka… a Bank) with offerings that include p2p payments, checking accounts, debit cards, stock, and crypto investing, and pilots including microlending.

I do not doubt that Cash App’s financial offerings will continue to expand until they have all the offerings you’d expect of a legacy bank like Chase (besides the physical branches, of course).

Square’s prominence in payments, sets them up to grow into a more general Super App. Of the dozen or so general ‘Super Apps’ around the world, most got their start in one of three categories:

Messaging/Social: WeChat, Line, Kakao, Zalo, (aspiring ones like WhatsApp)

Transportation/Delivery: Grab, Gojek, Careem, Rappi

Payments: Alipay, Paytm, Kaspi, (+ Cash App)

For the rest of this post, let’s focus on Square beyond banking.

Framing Square as a Super App:

There is a large extent to which a Super App rises to dominance because -- by the success of its first killer feature (messaging, transportation, or payments) -- it has a wider distribution than most/all other companies in its geographic market.

Super Apps can convince other companies to build on their platform because it’s a shortcut to a wide distribution for other products or services.

A (wordy) afterthought paragraph in my WhatsApp article sums this up:

Super Apps are like a government collecting a sales tax. Say Tencent takes a 5% cut of Didi rides hailed through WeChat. Didi won ride-hailing in China, in part because of the native WeChat integration following Tencent’s investment. In this analogy, WeChat native integration = “government infrastructure”, so paying the Super App tax is worth it.

It’s a bit like trading profit margin for distribution. [As developers already do with e.g., the Apple App store]

Even though Cash App is one of the most popular financial apps (across economic classes) in the US., it’s still a challenge for Cash App to offer distribution for other established companies (e.g., Uber, Starbucks, or Airbnb).

From How to Build a Super App:

Super Apps could simplistically be thought of as platform companies that are able to build out many verticals within one app. This has worked well in markets like China, Indonesia, etc. because those markets did not have strong incumbent competitors.

It’s a tougher sell to get established businesses to pay a Super App tax in the US. As the expansion of Super Apps shows:

The evolution from a regular app to a Super App looks something like this:

Build 1 killer app (WeChat: messaging) or a suite of complementary apps (Gojek: Motorcycles, taxi, delivery) in-house —>

Do some formal BD/Partnership deals where you allow a third-party to offer their services through your app (e.g., WeChat offering ride-hailing via Didi, Gojek offering medical product delivery via Halodoc) —>

Have a completely open product line where ANYONE can create their own app within your app (WeChat: Mini programs)

For the Cash App, there may be partnership opportunities (#2 in my framework) with established companies to build on top of the Cash App.

There is some precedent for what this could look like within the Cash App. For users of the Cash App’s debit card, they can activate “boosts” which give Cash Back at different merchants. Per Square’s 10k, “some Boosts are selected and funded by the Cash App team, while others will be funded by our partners”.

Instead of the boost just activating a discount within a debit card, they could take an approach similar to WeChat when it was getting mini-programs running,

“WeChat also tried something with McDonald's where you could buy a coupon voucher within WeChat and then show the QR code to your McDonalds Cashier to redeem the offer.”

That identical flow could happen with Cash App where users show a coupon to get a discount before paying. This would help get users familiar with the behavior of using the app, rather than just a debit card as a primary payment method.

That said, it’s just as likely to me that Cash App skips this step and focuses more on its existing base of small/medium-sized businesses allowing online and in-person merchants to have their stores live on top of the Cash App.

Oversimplifying a bit, in my WeChat issue, I described mini-programs as “a storefront built on top of a payments app, rather than a payment experience built into a website.” In line with Square’s roots of building hardware and software for merchants to streamline their operations, I envision a similar opportunity of ‘storefronts on top of the Cash App’.

Current Initiatives

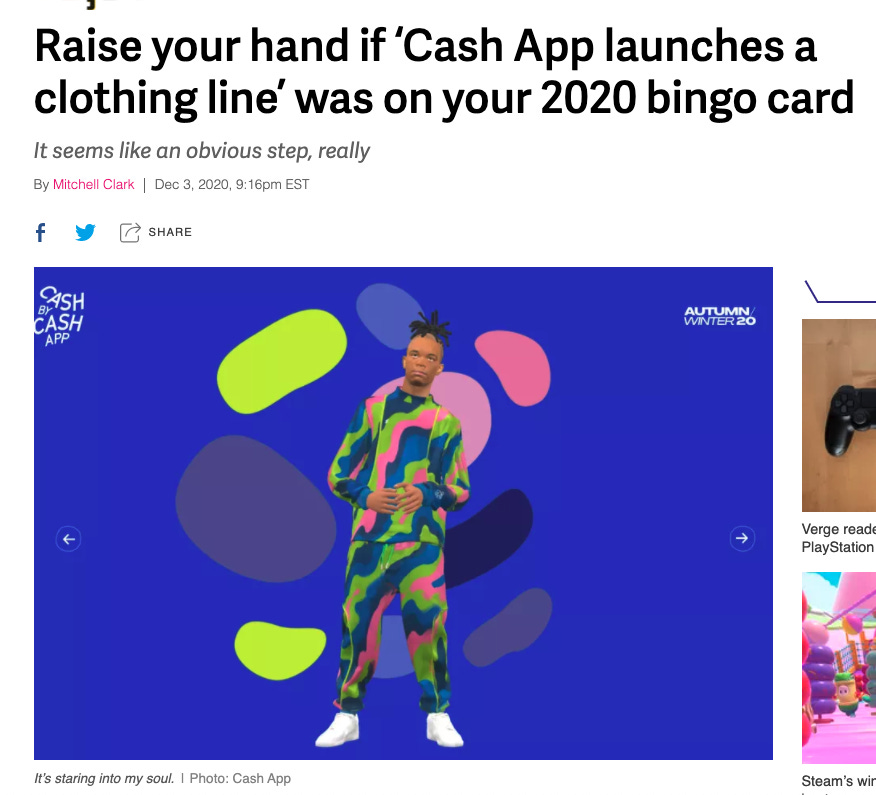

The Cash App Clothing Brand

Mini-programs were the first thing I thought of when I saw that the Cash App launched a clothing line.

While it’s possible this clothing line was nothing more than a customer acquisition strategy, I see hints of what shops on the Cash App could look like.

If you go to shop.cash.app on desktop, when you reach ‘payment information’ you can scan a QR code from your Cash App to quickly pay without needing to manually enter your payment information. (Check it out for yourself. It’s smooth)

Weebly and Website Builders

It’s also worth noting that the shop.cash.app site is built using Weebly, which – as a quick reminder – Square acquired in 2018.

One of Weebly’s investors included Tencent (of course).

At the time of investment, David Wallerstein who led Tencent’s investment said:

"The Internet is changing the future of business and entrepreneurship. Weebly is driving this transition to a mobile-driven e-commerce world with a platform that is just so simple and intuitive to use,"

Yup!

While Weebly does not seem to have taken over mobile e-commerce the way investors predicted, it is still extremely popular, especially with businesses with <50 employees in the restaurant and retail industries (very aligned industries with Square).

More generally, according to BuiltWith.com, it is the 4th most popular Simple Website Builder on the Entire Internet.

With a market cap of $100 billion+, Square has the ability to make some acquisitions, and expanding its site builder footprint to additional e-commerce players could be a worthy target. Many of the top e-commerce website builders are already accounted for. Let us assume that WooCommerce (owned by WordPress creator, Automattic), Magento (owned by Adobe), and public companies Shopify, Wix, BigCommerce are not available for sale.

Squarespace is one of the top website builders, specifically for e-commerce platforms, and overall, the top website builder in the US.

Square and Squarespace already have at least one partnership stemming back to November 2019 when Squarespace (which historically focused on e-commerce) integrated with Square’s POS software to better integrate offline (in-person) sales.

As was reported at the time:

This should excite small and medium-sized businesses, as we think Square offers some of the best POS hardware on the market, while Squarespace is one of the best website builders and ecommerce platforms out there.

While Square has a strong ‘offline’ presence with its terminals and footprint in the retail and restaurant industries, it’s ‘online’ payments penetration leaves a lot to be desired.

I stress this point because this O2O (“online-to-offline” as it is commonly referred to in China) was one of the big breakthroughs in WeChat’s transformation into a Super App, “WeChat also began partnering with physical businesses to offer online store functionality where in-person businesses could set up a digital storefront and sell goods.”

As of October 2020, Squarespace seems to be in the early stages of preparing to go public. It last raised funding in 2017 at a $1.7bn valuation (and is presumably, much more valuable today).

E-Commerce

Besides just forming a ‘Super App Strategy’ for the Cash App, some of these initiatives may be a way for Square to chip into Stripe’s lead in online commerce. Stripe and Square offer similar services to merchants, with Square having a stronger presence with physical businesses (restaurants, retail) and Stripe with a stronger presence with online merchants (“GDP of the internet”).

Conversion rates matter a lot for e-commerce. If Square can prove that Cash App’s QR code online payments (like from the Cash App Shop flow pictured earlier) convert at a much higher rate then that would be a compelling case to see Square’s e-commerce adoption increase, as well.

Existing Infrastructure

Like how WeChat and Alipay have interoperable hardware throughout China, many merchants throughout the US (and Canada, Australia, and Japan) have Square’s POS hardware in their stores.

Adding the option for all Square PoS hardware to be able to accept payment via a Cash App QR code seems like a quick path to widespread merchant adoption.

Square already acts as the operating system for small and medium-sized in-person businesses throughout the US. Square’s merchant business offers a wide range of services including, but not limited to:

Point of sale software

Square Appointments

Square for Retail

Square for Restaurants

Square Invoices,

Square Online Store

Square Payroll

Square Capital

+ All their hardware devices (card reader, the terminal, the register)

Grab and Gojek have both made merchants a core focus in terms of having a closed-loop system of people selling things, people delivering things, and people consuming things all while using their app’s native payment offerings.

Square can capitalize on a similar flywheel in which more merchants using Square’s payment solutions means more opportunities to convert employees to set up direct deposit to the Cash App, which leads to:

QR Codes

Generally, it seems like any previous ambitions Square had involving QR codes have been sped up as a result of COVID-19.

A November 2020 blog post from Square outlined all the ways merchants can currently use the Cash App and QR codes.

When a customer scans a QR code from a Square point-of-sale device, they can enter their card info or use Apple/Google Pay. There appears to be no option for the Cash App yet.

As a response to COVID, it seems Square has also introduced self-serve ordering where a customer sits down, scans a code, and orders without talking to a server. This is done for safety reasons but could lead to an enduring behavior change for restaurant ordering.

Using the Cash App Store as a benchmark, that same level of ease should be included for any merchants using Square’s PoS system with QR codes.

If you go to Shop.cash.app on mobile, it looks identical to the desktop flow I outlined above since the mobile flow just redirects to a webpage.

This flow should be streamlined for Cash App users by offering a native shopping and payments experience all within the Cash App.

There is nuance in how this page actually launches on a mobile device, whether it's more like:

An Instagram shop where you add a store’s product to an Instagram-managed cart and Instagram owns that flow?

Is it a Square-optimized equivalent of an Accelerated Mobile Page / Instant Article, i.e., a fast-loading HTML document that loads natively within the Cash App, but where the shopping cart is owned by the merchant?

Or is it closer to a mini-program? Which, involves some custom code and feels much more native than e.g., a Facebook Instant Article.

No clear answer, but my gut says #2. This allows stores to adopt their existing Weebly/SquareSpace checkout flows directly to the Cash App and mobile. If the merchant doesn’t have a Cash App-optimized mini-program, then it opens a normal website that users can go through a similar flow with.

To possibly give some additional insight into Square’s ambitions within restaurants, Patent Drop highlighted that Square recently dusted off a patent for “location-based transaction completion” within restaurants.

When someone has finished eating their food, Square describes the customer being able to open up their phone, request a bill through an app, and then automatically receive the correct bill from the Square merchant device by using the customer’s location information.

Each table would have a wireless beacon that transmits the location information of the buyer. When the buyer requests their bill, their phone will automatically pick up their table number and then submit this information to the merchant device.

That seems cumbersome when an alternative flow could be as simple as:

You get to your table and scan a QR code that opens up a Cash App mini-program menu

You add items to your cart and pay directly from the Cash App

Since the QR code is associated with your table, the server knows exactly where to deliver the food.

(That precise flow is one I ran into at a fast-casual restaurant in Shenzhen, China. Since I didn’t have WeChat Pay or Alipay at the time, I wasn’t even able to order and had to have my friend order and pay for me)

Square’s adoption with millions of merchants, puts them in a particularly competitive position to drive change at scale for restaurants in the “post-COVID world”.

Delivery:

It’s interesting to think about Square’s prior Caviar acquisition (and eventual Caviar sale to DoorDash) in light of a Super App strategy.

In 2016, addressing Caviar, Dorsey said,

Any of those Caviar restaurants could eventually take advantage of Square services as well, and this is how we think about our ecosystem — it’s not just one product but they all work better together."

At the time, Dorsey seems to have viewed Caviar as an acquisition tool for Square’s core merchant business.

At present, there are two paths for merchants to manage delivery via Square:

A merchant’s Square terminal aggregates all the different delivery service APIs so that you don’t have a scenario like the photo below

More interesting is the June 2020 announcement of “On-Demand Delivery for Square Online Store sellers”

In this on-demand model, a customer can go to a restaurant's website (e.g., Kebab Shop) and order delivery directly from a restaurant’s website without ever knowing which delivery company is being used. This is great for merchants as it allows them to maintain a direct relationship with the customer, whereas if they used one of the delivery services, they would not receive the customer information.

A subtle point of why Square can do this is because they are not competing with restaurants for customer information. Square is very happy to allow restaurants to own customers’ email, phone numbers, etc. As they highlight in the release of “On-Demand Delivery”

“Additionally, when buyers place an order through Square Online Store, sellers receive their contact information in the Square Customer Directory and are able to maintain sales history for those customers. When paired with other products like Square Marketing and Square Loyalty, sellers can strengthen customer relationships, create open lines of communication, and incentivize patrons to keep coming back.”

Square grows with their merchants (and charges for value-added services). If a merchant is growing their business and rolodex of customers, while using “Square marketing” and “Square loyalty”, Square is happy.

Square can charge its standard processing fees, a flat $1.50 per on-demand delivery fee, AND commoditize the delivery aspect to companies that specialize in that. Interestingly, Square’s first partner on this is Postmates (not DoorDash/Caviar).

While it would be a challenge for an established app like DoorDash to live on top of the Cash App, I could imagine the Cash App offering a “restaurant” tab in their app that shows you local restaurants (only those using Square Merchant services) and you can order, check out via Cash App, and have it delivered via a suite of competing delivery vendors (Postmates, Caviar) all within the Cash App.

I think it’s tough for any one of the delivery platforms to engender real customer loyalty (though DashPash and Uber Pass are stepping in the right direction).

Wrapping Up

Competition

While writing this I thought to myself, what would stop other neo-Banks from copying this playbook? Revolut, for example, has very public ambitions of being a “financial Super App”.

However, what no other competitor has is an existing network of millions of merchants already using their payments services.

Square is unique in terms of having a well-adopted B2B product, hardware deployed all around the country, and a wildly popular consumer app.

Where could this be wrong?

Everything you read above is me projecting my own ideas and the concepts of this newsletter onto Square

Shop.cash.app is just an attempt at a unique channel for Cash App customer acquisition. It’s not a prototype of what a storefront on top of the Cash App could look like

There’s an open question whether restrictions from Apple App Store and Google Play stores would allow Square to offer a competitive service on their devices

It's TBD whether QR code payments will (or should) be widely adopted in the US when NFC payments seem to be more prevalent and secure.

Conclusion

At a time when small and medium-sized businesses are struggling, the Cash App could offer an opportunity for local shops to easily digitize and more profitably sell goods online while creating an extremely powerful moat and ecosystem, integrating their B2B and consumer products.

If you liked this article, please consider giving it a “❤️” on Substack or sharing it with friends!