China's P2P Bubble and Lufax

Poor financial controls, bubbles, and a $40bn Ant Group competitor

Housekeeping:

Thanks again to the wonderful folks at TechinAsia.com, this time for republishing my article making the case for WhatsApp as a SuperApp (slightly edited TiA version, original)

If you enjoy this post or any other posts, please consider sharing, commenting, or just giving the post a “❤️” on Substack.

Today’s Rundown:

A history of peer-to-peer (P2P) lending and financial bubbles in China

An overview of Lufax, which survived the bubble and just went public in the US

New Section: News Recap

Short subscriber survey

The history of P2P lending in China is riddled with conflicting information, tough to understand regulations, and many pieces are still unfolding (as you will see in the news section!)

Introduction

On October 29, 2020, Lufax, a Chinese online lender, raised $2.4 billion in one of 2020’s largest U.S. IPOs. The company is valued at $40 billion+.

The 13-years between the start of the peer-to-peer (P2P) lending industry in China and the Lufax IPO are a true rollercoaster.

In 2006, China’s first peer-to-peer (p2p) lending company, CreditEase launched. This was on the back of the launch of Zopa in the UK in 2005 and LendingClub in the US in 2006.

In its purest form (and to oversimplify a bit), P2P lending is connecting people that have capital directly with people who need capital. While the connector will usually charge some fee, part of the promise is that you are still cutting out a more extractive middle man (often a bank).

For lenders, the benefit is that you can earn a higher rate of return by lending directly to someone on a P2P platform than you would by depositing your funds in a bank (which would also lend out the capital but would keep most of the yield for itself).

The borrowers who benefit most from P2P platforms are people who would otherwise not be approved for a bank loan, in general, these are riskier clients

China’s financial industry (circa ’05 – ’15) was particularly well-suited for P2P and micro-lending.

China’s (mostly) state-owned banks were very risk-averse and historically did not lend money to individuals and small businesses. In fact, they mostly only loaned money to other state-owned entities.

China lacked an established credit bureau so there was minimal credit history data, which made vetting borrowers tough.

China boasted (and still does boast) a high average savings rate but -- especially in the early 2010s -- did not have robust investment opportunities. For perspective, the average savings rate in China is between 40-50%, compared to the U.S. where it is <10%.

The P2P industry was willing to take on risk and provide credit to individuals and small businesses, while also offering high yield investment opportunities to China’s millions of savers.

I’ve read highly conflicting numbers, but near the peak in 2016/2017, there were somewhere between 4,000 – 7,000 P2P and micro-lending platforms operating in China, doing nearly 130 billion RMB ($19 billion) in volume per month.

There was a big opportunity to do something meaningful and expand the lending market in China to more individuals and small businesses. But the frenzy got the best of people. Like any good speculative bubble, the industry quickly attracted many fraudsters.

There were all kinds of things wrong with how the industry was being run in China. Corporate funds were co-mingled with funds that were supposed to be segregated for borrowers, returns were guaranteed by the companies, and companies were rarely acting as just a matchmaker or escrow agent of the client funds. Without any kind of standards, purely fraudulent entities were able to amass billions of dollars of customer funds.

The problems of the industry were best displayed by the industry’s leader in 2016, Ezubo.

Ezubo

The biggest blow-up happened in February 2016, when it was uncovered that Ezubo, which was the largest P2P lender in China at the time, was actually a giant Ponzi scheme.

At its height, Ezubo had raised RMB 59 billion (US$9 billion) from nearly 1,000,000 individuals throughout China.

As the Beijing police said:

“Ezubo had lured investors with promises of high-interest payouts from leasing projects. It quoted company officials saying 95% of the advertised investment projects were falsified and calling Ezubo “a downright Ponzi scheme.”

As the WSJ showed at the time, investors lined up at government offices to try and get recourse for their lost funds

Today, Ezubo’s founders are serving life sentences in prison while 25 former employees are serving sentences of 3-15 years. At the time of arrest, the company had failed to meet repayments on RMB 38 billion (US$5.7 billion).

In reality, Ezubo was not doing P2P lending in the way it is widely understood. They told lenders that they’d be offering ‘finance leasing’ where Ezubo would buy manufacturing equipment using the lenders’ money and then lease that equipment to e.g., farmers who would provide a stream of income from leasing payments. Annual yields were quoted in the 9-15% range.

Now, from what I’ve read on Ponzi schemes, they seem to start in one of two ways:

It does not start as a Ponzi, but something goes wrong (back-to-back bad quarters) and a firm can’t meet its expectations or obligations. The firm then brings in new money to pay off the old money and the process repeats from there. They say, “We just need to do this for one more quarter until we make enough money to get back to breakeven”, but that never happens.

OR From day one, the company decides that it will not have legitimate business operations and that it will lie to consumers about how it generates yield and will only operate a Ponzi scheme.

I feel like you don’t see many of #2.

It’s even debated what Bernie Madoff was, but the speculation I recall was that he was a case of #1 where he started as a legitimate operation and became a Ponzi after a few decades of trading.

Ezubo seemed to be a case of #2.

Again, from the WSJ:

“prosecutors said that Ezubo didn’t invest the money it collected, but rather used it to pay down earlier debt—and to fund lavish lifestyles for [the CEO] and several female executives. Mr. Ding [the CEO] allegedly gave one favored colleague a 130 million-yuan ($19.7 million) villa in Singapore, a pink diamond worth 12 million-yuan ($1.8 million), luxury cars and 550 million yuan ($82.5 million) in cash.”

Really, not even trying.

Following Ezubo’s demise, the cracks in other platforms began to show. Between June and July of 2018, a total of about 250 P2P platforms defaulted.

Lenders, who normally had to wait for the term of their loan to expire before receiving back their principal + interest were “trying to exit early by selling their rights to others at a discount, or by going to the platform’s offices to demand repayment.”

In one extreme, local authorities in Hangzhou, China converted two sports stadiums into a center where aggrieved P2P lenders could file claims with local authorities against the companies that had disappeared with their funds.

It got to the point that even a state-sponsored P2P platform, Huoq, disappeared.

Huoq launched in December 2016 with backing from state-owned Chinese enterprises, it then went into liquidation in July 2018, and the founders disappeared with no one able to find them.

These ‘exit scams’ were common.

Blomberg recounted one users’ story at the time,

“David Gao, 30, who works in the financial industry in Beijing, invested 1 million yuan (US$150,000) of his savings in P2P loans facilitated by a Hangzhou-based platform in November and has been unable to retrieve his principal and interest. After traveling 700 miles to the company’s office with other investors last week, he found it deserted.”

☹️

Regulation

Following the Ezubo blow-up, regulators finally stepped in with restrictions that included:

Limits on the amount individuals could borrow from one platform ($30,000) and could borrow in total ($150,000)

Platforms needed to stop offering complementary products (e.g., insurance, wealth management)

Platforms could only serve the role of matching borrowers and lenders (i.e., they could not take on principal risk, had to stop repackaging and selling loans)

Platforms could not guarantee returns

Platforms needed to work with qualified custodians (e.g., banks) to hold users funds, meaning platforms could no longer co-mingle loans with corporate capital

Following these regulations, it stripped the P2P companies of their ability to operate as ‘shadow banks’ (That is, “non-bank financial intermediaries that provide services similar to traditional commercial banks but outside normal banking regulations.”)

The biggest challenge on the business models of these platforms imposed by the regulations was that they banned these P2P platforms from doing anything other than matching borrowers and lenders.

Like many modern FinTech products globally, China’s P2P platforms began by offering one financial service (P2P) and then added more services until they were able to offer a suite of financial products and services.

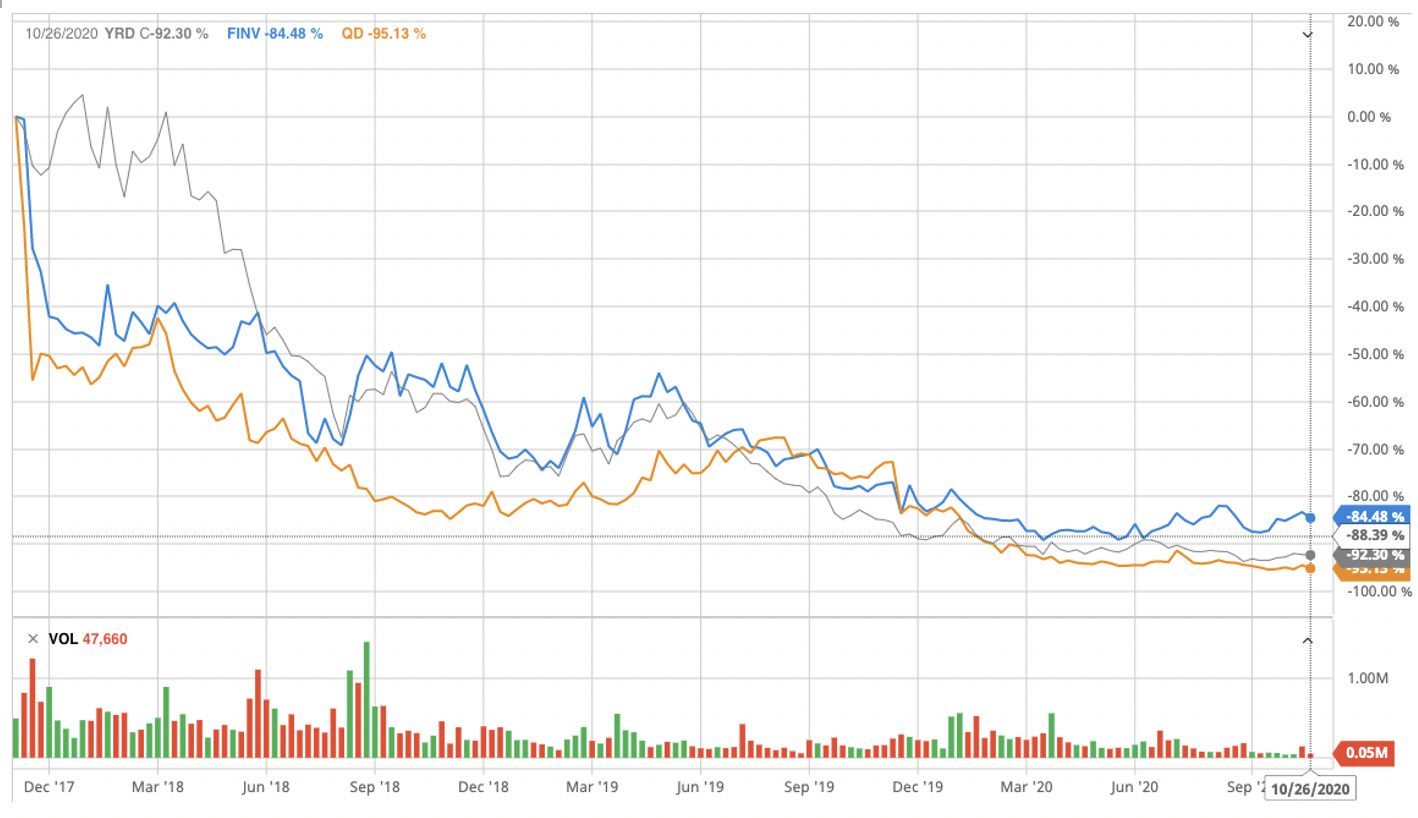

Of the thousands of companies that were founded to capitalize on P2P lending in China, four of them have made it public in the US stock markets. These include:

Yirendai (NYSE: YRD, $305M Market cap)

PPDAI (NYSE: FINV, $383M Market cap)

Qudian (NYSE: QD, $340M Market Cap)

And then most recently, Lufax (NYSE: LU, ~$40 billion+ market cap).

Yirendai, PPDAI, and Qudian — which all went public between 2015 and 2017 — are down between 80-100% from their 2017 highs.

Lufax is impressive in its ability to go through several reinventions to be able to thrive in a way that the other companies above have not been able to, but it still faces steep headwinds.

Lufax:

After 20 years at McKinsey, culminating as a Senior Partner in the firm’s greater China practice and a stint as COO at a Taiwanese public company, Gregory Gibb took on the role of ‘Chief Innovation Officer’ at Ping An.

Ping An is one of the largest companies in the world and is China’s largest insurance company and conglomerate of financial, tech, and healthcare services. When Greg stepped into the role in 2011, he was quickly tasked with building Ping An’s P2P lending product, and thus, Lufax was born with Greg taking over as the CEO and Co-Chairman.

With the support of Ping An, Lufax quickly rose to become China’s largest P2P lender as Ezubo was going through its blowup. Compared to their upstart competitors, Lufax was able to offer a higher level of trust, since they were able to (actually) guarantee loans as a result of Ping An’s balance sheet.

Lufax always viewed their role as more than just a facilitator of P2P lending. As far back as 2014, Gibb was saying that the goal was to build a large wealth management business and upsell Ping An products, using P2P as a cheap customer acquisition channel.

In 2015, Lufax’s product offerings were pretty straightforward, with both P2P and wealth management products.

These included:

WenYing-An-e - an unsecured P2P loan with an average maturity of 1-3 years, a minimum investment amount of $1,500, and a project annualized interest rate of 7.84%+

WenYing-AnYe - a “real-estate-mortgaged” investment product with an average maturity of 3-12 months, an investment minimum of $37,500, and a projected interest rate of 7.5%-7.8%

FuYing RenSheng – An investment product for senior citizens with a minimum investment amount of $150, a projected annual rate of return of 5.5%, and a 3-12-month duration

“Exclusive Wealth Management” – An investment product for preferred members with a 15K minimum, 1-12-month duration, and expected annual returns of 15-20%.

These were likely generally indicative of other products that were on the market at the time.

Today lending and wealth management have basically an equal number of users at Lufax, but wealth management generates far fewer revenues.

The interesting story to be told in the lending numbers is the shift between the percentage of loans funded by third-parties (presumably, banks) vs. the percentage funded by Lufax.

In 2017 when the Chinese government added requirements that businesses become mere matchmakers of borrowers and lenders, Lufax was able to adjust faster than their competitors (likely stemming from their parent company’s existing relationships).

As shown below, starting in 2017, the percentage of loans funded by Lufax vs third-parties went from about 50/50 in 2017 to nearly 100/0 in 2019.

Today, Lufax is the second largest (non-bank) provider of consumer and small business loans in China, behind only Ant Group.

In the (non-bank) wealth management business, they are the third-largest in China behind Ant Group and Tencent’s Licaitong (both covered in earlier issues on Ant and WeChat).

As a % of market share, Lufax is a distant second in consumer lending, a distant third in wealth management, but a close second in small business loans. Lufax also has much larger loan sizes than its competitors, again likely as a result of the support of its largest shareholder, Ping An.

Lufax’s business is much more financial services and much less tech than the businesses of Ant and Tencent. This makes sense putting the numbers above into context. They don’t have as many customers as Ant or Tencent, but they do have larger loan amounts.

The worst dimension on which Lufax is different than the FinTech offerings from Ant and Tencent is that it does not have the same differentiated distribution channels that Ant Group (via Alipay) and Tencent (via WeChat) do. As a result, Lufax looks more like a traditional financial institution. As an illustrative example, compare the headcounts of Lufax and Ant Group.

Lufax employs about 5x as many total employees as Ant does with most of them in sales and marketing. Lufax also employs only about 1/10 the number of tech and R&D employees as Ant Group does.

Of the 66,700 sales and marketing employees at Lufax,

56,764 are in direct sales

5,078 are in channel management

4,239 are in online sales

Lufax has 695 offices in China. Presumably, most of this is not ‘corporate office space’, but is inclusive of call-centers for its telemarketing staff and the fact that Lufax operates ~100 storefronts throughout China to complement its large salesforce.

The direct sales seem to work though, with 45% of Lufax’s 2019 loans (USD $33 billion) coming through that channel. Online and telemarketing accounted for the least number of new loans, only ~12% of the 2019 total.

Generally good for companies like Lufax is the fact that household debt is quickly rising in China. The increased propensity for consumers in China to take on debt along with small businesses potentially needing loans while rebounding from COVID could be a boon for Lufax’s business.

Conclusion

Lufax deserves a ton of credit for competing against China’s two giants, Alibaba (Ant Group) and Tencent, and remaining competitive. And we should also not discount the head start they were given from their majority shareholder, Ping An.

Something generally to note about Lufax that is similar to Ant and WeChat is that all of them started within or with the support of existing giant companies. Ant is a semi-spinout of Alibaba, Lufax was started within and with the support of Ping An Group, and WeChat (and its FinTech offerings) was birthed within Tencent.

It’s tough to make a bet on Lufax in the face of Ant Group and Tencent’s wealth management and credit products. Lufax becomes a clearer bet if China continues to pursue antitrust actions against Alibaba and Tencent.

That said, Lufax is vulnerable to any additional restrictions that the government puts on the rates they are able to charge on loans. It’s also possible that CCP restrictions intended to harm Ant could hurt Lufax as collateral damage.

For now at least, as the Ant Group IPO was suspended and Chinese regulators announced they’d begin to focus on anti-competitive behaviors in the tech industry, Lufax shares rose as shares of Alibaba and Tencent fell.

News Recap

Since many of the companies I’ve done deep dives on (Grab, Gojek, Tencent Music) are still very much writing their histories, I want to use this section to highlight interesting news from each along with other Asia news that I think should be on your radar.

China’s P2P and an SF-based Crypto lending company (Bloomberg, Cryptobriefing, Coindesk)

While I was writing this article, another company with ties to China’s P2P industry blew up.

Cred, a San Francisco-based crypto company that offers you yield on idle cryptos (i.e., they will pay you 8% annually if you lend them your bitcoin) filed for bankruptcy.

Cred generates yield by taking the Bitcoin you lend them and then lending it to other partners who will pay Cred 10%+. Cred keeps the spread between the 8% they promise depositors and what borrowers pay Cred.

It was revealed in the bankruptcy filings that one of the companies Cred was using to generate yield was moKredit, a P2P lending company in China that funds gamers for their purchases of in-game items and such.

MoKredit and Cred share a common co-founder.

MoKredit is on the hook to Cred for ~$40 million (!!).

The link above from Cryptobriefing is particularly good with on-the-record comments from former employees of Cred

Tencent Music (TME) posted better than excepted revenue and subscriber numbers in Q3. (Reuters, Tencent IR)

As covered, compared to Spotify, TME drives most of its revenues from social-entertainment functions, not premium subscriptions.

By year-end, TME hopes to move 20% of their content behind a premium paywall

In mid-2018, TME had ~23M paid subscribers. Today that figure is growing faster than analysts anticipated with 51.7M premium music subscribers (and 599.3M free music subscribers)

Live-Shopping App Popshop wins $100M valuation from Benchmark Capital (The Information$)

Popshop has been described as “QVC on mobile” and is likely drawing influence from many of the social commerce trends that have succeeded in China such as Taobao Live and Pinduoduo’s Duoduo Livestreaming.

It was reported that this funding round was extremely competitive between two of Silicon Valley’s best firms, Benchmark Capital and Andreessen Horowitz.

Popshop is a good example of one of the main themes of this newsletter:

In Zero to One, Peter Thiel said, "The easiest way for China to grow is to relentlessly copy what has already worked in the West.” At some point, that was true. However, I don’t think it’s true anymore. Already, Western technology companies, especially consumer-focused companies, are looking to China and SEA to copy ideas coming from Asia’s best entrepreneurs.

More often, we will see western technology companies “relentlessly copy what has already worked in the [East]”

Super Apps and Payments: Grab leads Series B of Indonesian Fintech LinkAja (TechInAsia)

As TiA says, “LinkAja is founded by Indonesian state-owned enterprises, Grab could have access to the country’s train and highway toll payments, utility bills, and social welfare distribution, among others, while LinkAja will benefit from Grab’s reach and technological expertise.”

The end goal of a full-fledged Super App is a touchpoint throughout a consumer’s entire day. Said another way, Super Apps want to take a tax on all of a consumer’s transactions. Payments are an integral part of that, from public transport to buying a coffee, or importantly, things you do without thinking like paying a bill.

Indonesia is one of the biggest countries up for grabs (ba-dum-tss🥁) in Southeast Asia and Grab continues to crack away at Gojek’s lead there.

Ant Group IPO suspended (WSJ):

In the draft of my Ant Group piece, I had a line that didn’t make it into production, about how one of the toughest aspects of investing in businesses in China was the unpredictability of China’s regulatory regimes. I’m bummed I cut that line.

On November 3, the Ant Group IPO was suspended as a result of a speech that Jack Ma made that was critical of the CCP and state-owned financial institutions. The decree to halt the IPO came directly from Xi Jinping.

If I were Trump, I’d be on the phone trying to bring the Ant Financial IPO to the US markets. This could, long-term, of course, wind up being far worse for Ant if the CCP took that as the ultimate sleight and launched an even more direct retaliation.

There is a ton to unpack in this story, but one of the savvier moves from Chinese regulators to really ding Ant is that they will require them to not just be a tech platform, but also take on more bank-like functions (such as funding their own loans). Ant spent the past few years trying to not look like a financial institution (to get that sweet sweet tech multiple) and now the Chinese regulators are forcing them to look more like a bank.

This is interesting for tons of reasons. Not least of which because you have one of the most powerful men in the world (Xi) facing off directly against the richest man in China (Jack Ma).

A quote from the WSJ,

“Xi doesn’t care about if you made any of those rich lists or not,” said a senior Chinese official. “What he cares about is what you do after you get rich, and whether you’re aligning your interests with the state’s interests.”

Do you have feedback? Please fill out this short Google Form. It will help me improve the newsletter! LINK

As always, thank you for reading,

@ryanrodenbaugh